It’s a common enough experience that it has a tidy psychological description - “the illusion of independent agency.” You, the author, minding your own business as you shuffle your characters about like pieces on a chess board, bending them to the will of your meticulously designed plot, are faced with a sudden rebellion. Your character - your very own creation - refuses to do what they need to do. Try as you might, you simply cannot get them to comply: they stall, they balk, they talk back to you and demand all sorts of concessions if they’re going to go through with the actions that you insist are necessary for the story to progress. Indeed, they start to tell you that your story is wrong, that they have a different story to tell, and you, the author, had better sit down and listen, because they will not be quiet until their story is told.

I’ve been struggling with this so-called “illusion” as I work on the follow-up stories to “Off the Leash”, part of the Mapping the Boundaries of Love series. Indeed, it first showed up while I was writing “Off the Leash,” when a character I hadn’t anticipated made an appearance and demanded that his story be told. Before then, I expected “Off the Leash” and “A Dip in the Lake” to come out as a single volume with alternating chapters: we’d see what Phil and Jessie were up to on their lost weekend in the woods, and then what Petra (Phil’s fiancee) was doing at the swingers’ convention that takes over her girls’ getaway weekend at the casino. The conclusion would be a reconciliation between our wayward lovers and a celebration of monogamous passion, maybe with some hot Phil-on-Petra action. As soon as I saw Martin’s diamond ear stud and debonair beard, and as soon as he let me know that his favorite drink was the Godfather, I knew that my one book story was actually three, and I needed to get to know Martin a lot better.

When I started working on the expanded version of Petra’s story, which became “Off the Leash”, Petra’s friends started demanding their own stories, too. They did this mostly through references to off-the-page moments that intrigued me. When Madeline meets up with Petra and Casey after the first seminar presentation that Martin gives, with her friend Kelsey in tow, I knew I had to know more. She was already an interesting character in the story as originally imagined — she hires a male stripper before the three friends have even finished unpacking in their hotel suite, for goodness sake! — but her off-the-page antics suggested that there was a lot more going on than I had suspected. When she shows up a little later wearing nothing but blue body paint, I was absolutely hooked: Madeline, a sort of manic-pixie-dream-girl-on-steroids, angling for an epic gangbang to cap a wild weekend as a swinger couple’s unicorn, definitely needed her own story.

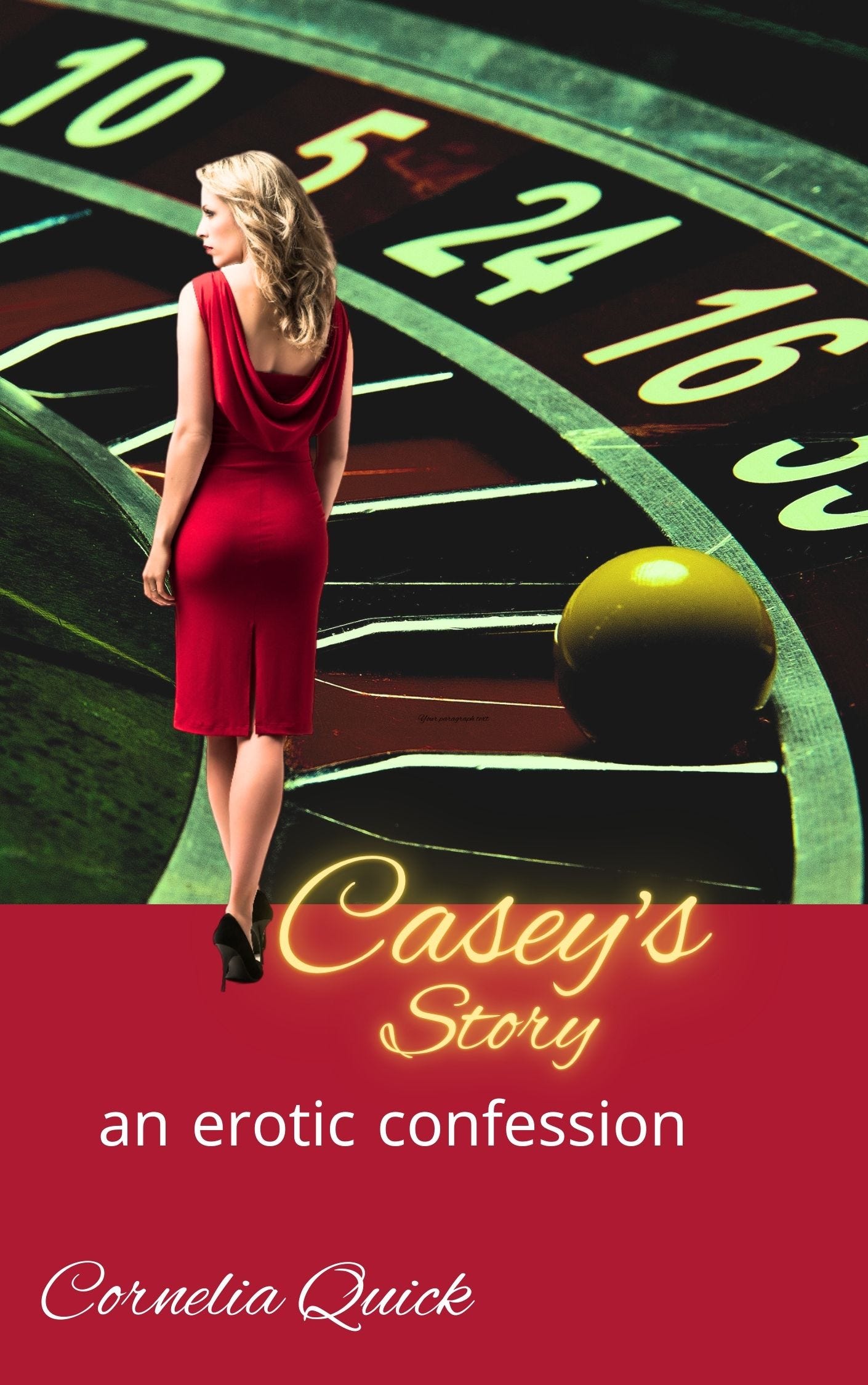

Casey was a quieter, and more insidious, character. When Madeline got her own story (“Madeline’s Awakening”), it seemed only fair that she should get her own story, too. But in “Off the Leash,” she doesn’t do a whole lot: she’s the steady, mature, slightly older friend who dismisses Petra’s misgivings as so much unnecessary angst and encourages Petra to sow some wild oats. When Petra discovers her asleep in bed with Madeline curled up against her, though, I knew there was more to Casey than met the eye.

We get a little more — well, a lot more — of Casey in “Madeline’s Awakening”, when the clit-tickler vibrator Casey bought in “Off the Leash” makes an appearance. That was the first sign, to me, that Casey had some hidden kinks and wrinkles that warranted a closer look. As I look back over both manuscripts, though, I see that she had been dropping clues all along that she wasn’t nearly the innocent mother figure we think she is.

That’s my experience of “the illusion of independent agency”; but what about the phenomenon itself?

The academic literature compares the experience to childhood “imaginary friends,” and references some lab studies in which children with imaginary friends are given opportunities to experience their friends’ autonomy, such as when the researchers give the “friend” a gift and state that the “friend” refuses the share. What I found interesting in those studies, as related in a LitHub.com article by Jim Davies, is that the children were peeved at the researchers’ attempts to hijack their imaginary friends. The subjects were perfectly happy to argue with their imaginary friends, and didn’t feel in control of their friends’ behaviors, but they sure as hell weren’t going to let some headshrinker dictate the terms of their relationship.

I had some imaginary friends as a kid, mostly embodied in my dolls and stuffed animals, and they certainly had personalities independent of my own. Even now I can recall their personality traits just by bringing those particular toys to mind; they had relationships not just with me, but with each other, and it was these independent relationships that I found most fascinating. Sometimes they called on me to resolve disputes and settle disagreements, but usually I was content to watch their interactions progress at their own pace.

Western psychology wants to infantilize the experience, naturally enough, seeing in it immature wish fulfillment and unconscious immature impulses. Surely no fully-grown, rational, mature adult would put much credence in an experience like “the illusion of independent agency.” It is, after all, an illusion — it’s right there in the name, can’t you see?

Which strikes me as assertion without evidence. Consciousness is such a strange, slippery experience that no one has been able to pin down in any meaningful way; who’s to say what is illusion and what is not, when it comes to the creative process?

For me, it feels a lot more like a cross between animism and spiritualism than any sort of “illusion” (both of which, of course, western psychology would categorize in the “illusion” bucket; but whatever …). Imagination often feels like it’s tapping into reserves of power that are outside the normal, measurable boundaries of experience; we can conjure up images, people, places, things, in such robust detail that they might as well be real. They’re certainly as real in our minds as memories of things that are long past, or imaginings of things that may be real but that we’ve never experienced directly. I would direct the curious toward George Berkeley’s philosophy of idealism — perhaps a bit more solipsistic in its repercussions than I might fully sign on to, but not a bad starting point in centering the mind and perception in our experience of the world.

We are, after all, creatures of mind to a great extent. Our perception of reality is as important as reality itself in most of our daily interactions with the world. While we certainly can’t think our ways around a speeding train or a falling piano, how we imagine our world has a surprisingly cogent effect on how we experience our world. I’m sure that I’m not alone in having had a dream — good or bad — affect my perception of my waking day, and color every decision I make; the most immaterial, unreal experience can be made real by our choices. Reading and writing are very dreamlike states, at least for me — I am often surprised, for example, when I’m writing a scene that takes place during a stormy night, to look up and find myself bathed in soft morning light. That a character might step out of that storm that I spun up out of pure imagination, and have words with me that feel entirely independent of my direction, does not seem strange at all. Unsettling, perhaps, but not strange.

My own literary interests have long been in American and Irish Modernism, and literary movements that drew on those strains. And a big part of both traditions — sometimes forcefully denied, sometimes wholeheartedly embraced — was spiritualism and the practice of automatic writing. I’m thinking in particular of figures like William Butler Yeats (and his wife Georgie Hyde-Lees, an underrated genius in her own right), Andre Breton, and William Burroughs, who achieved fascinating, if uneven, results when they let their conscious minds surrender to the unconscious. It’s not unusual, at least in my experience, to attain a sort of trance-like state in the middle of writing, where flow is achieved and it feels as though you’re transcribing events that you’re witnessing and not describing the output of an overactive imagination.

And believe me, this can happen as easily writing smut as it does writing loftier kinds of fiction.

Do I think Casey is a “real” person? Well, it all depends on what you mean by “real.” Is she a person I can call upon to help me wash the dishes, walk the dogs, or pay the bills? Alas, no. But is she a person who can express opinions that are distinct from my own, and insist that the facts as she experiences them are different from the facts as I originally imaged them? Oh, very much so. And it’s really in my best interest to listen to her, which is why this particular book is behind my self-imposed schedule.